Table of Contents |

Introduction

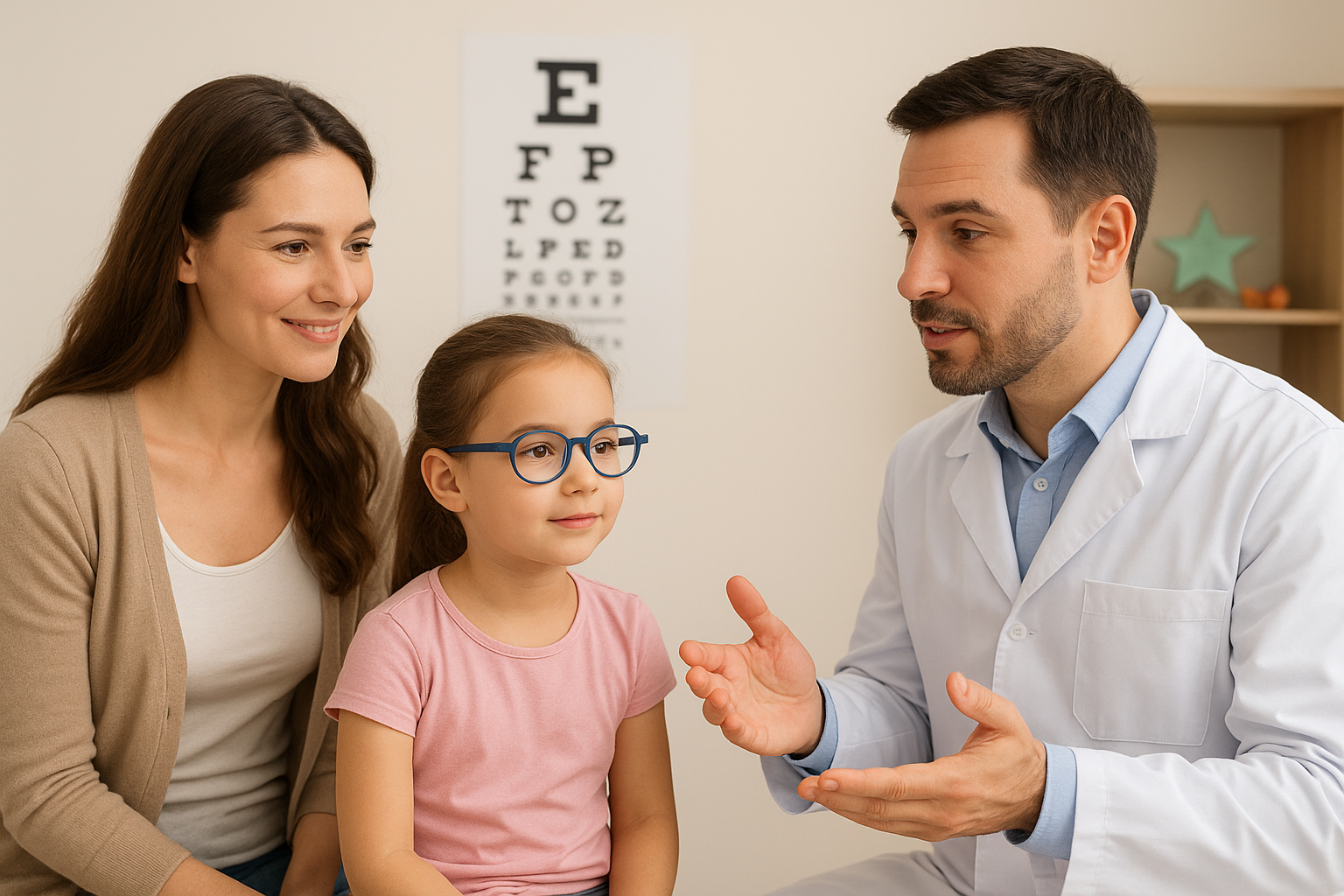

By virtue of my specialization in pediatric ophthalmology, strabismus and neuro-ophthalmology, I get to see a large number of children with mental retardation and visual impairment in my clinic. In a lot of such situations, this is their first visit to an ophthalmologist as the parents have been busy with managing the developmental delay and have been visiting the paediatrician. It is generally when a paediatrician or paediatric neurologist sees them and refers them to me that the parents begin to realise there is something wrong with the child’s eyes.

Identifying Eye Abnormalities That Reveal Broader Developmental Issues

- Parental Observations: Parents sometimes notice a lack of eye contact, disinterest in surroundings, or visible eye abnormalities such as squint or cataract.

- Clinical Finding: Eye examination often reveals generalized developmental delays extending beyond an isolated eye disease.

- Referral Approach: These children require referral to pediatric neurologists for comprehensive assessment and diagnosis.

- Management Needs: Both groups demand multidisciplinary care, involving low vision rehabilitation and broader therapies for development.

- Specialist Role: Vision rehabilitation specialists highlight early detection for initiating visual rehabilitation therapy at a center for visual rehabilitation.

Case History: Birth Complications and Early Signs of Developmental Delay

- Initial Referral: A 14-month-old boy with hypoxia at birth was referred to the ophthalmologist with developmental delays and visual issues.

- Labour Complications: Prolonged induced labour with fetal distress and meconium-stained liquor complicated delivery.

- Delivery and Birth: Forceps-assisted delivery with post-birth resuscitation was necessary for the cyanosed, limp newborn.

- Early Development: Feeding was adequate, but milestones like neck holding, eye fixation, and interaction were delayed by 6 months.

- Progress at One Year: Limited head control, minimal sitting support, sound articulation without words, and persistent abnormal eye movements.

- Neurological Workup: MRI revealed gliotic brain changes due to hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; ENT confirmed normal BERA hearing tests.

- Specialist Referral: Child was referred to ophthalmology for eye examination and possible visual rehabilitation for children.

Comprehensive Eye Examination: Identifying the Cause of Poor Vision

- Visual Check: Child perceived the torchlight but failed to fixate or follow, indicating significantly poor vision.

- Eye Movements: Presence of nystagmus in both eyes with poor fixation on visual charts supported cortical dysfunction.

- Pupil Reflexes: Pupillary reflexes were brisk and normal, ruling out optic nerve pathology.

- Eye Health: Dilated examination showed no cataracts or retinal issues, confirming cortical visual loss from encephalopathy.

- Refractive Error: Retinoscopy revealed high hypermetropia (+10), raising the possibility of ametropic amblyopia.

- Next Step: Planned cycloplegic retinoscopy for accurate prescription, critical in effective vision rehabilitation.

Parental Guidance and Steps for Early Visual Rehabilitation

- Counseling Need: Parents advised repeat checkup with atropine retinoscopy to confirm precise refractive correction.

- Amblyopia Risk: Without glasses, the child risked permanent amblyopia; parents were initially reluctant to accept.

- Rehabilitation Perspective: Glasses could improve environmental interaction, supporting visual rehabilitation therapy and neurodevelopment.

- Consistency Message: Emphasis that consistent spectacle wear is essential for progress in vision rehabilitation for children.

- Practical Guidance: Advised use of safe polycarbonate lenses with straps for child comfort and safety.

- Specialist Support: Vision rehabilitation specialist educating parents improved acceptance and commitment to the rehabilitation plan.

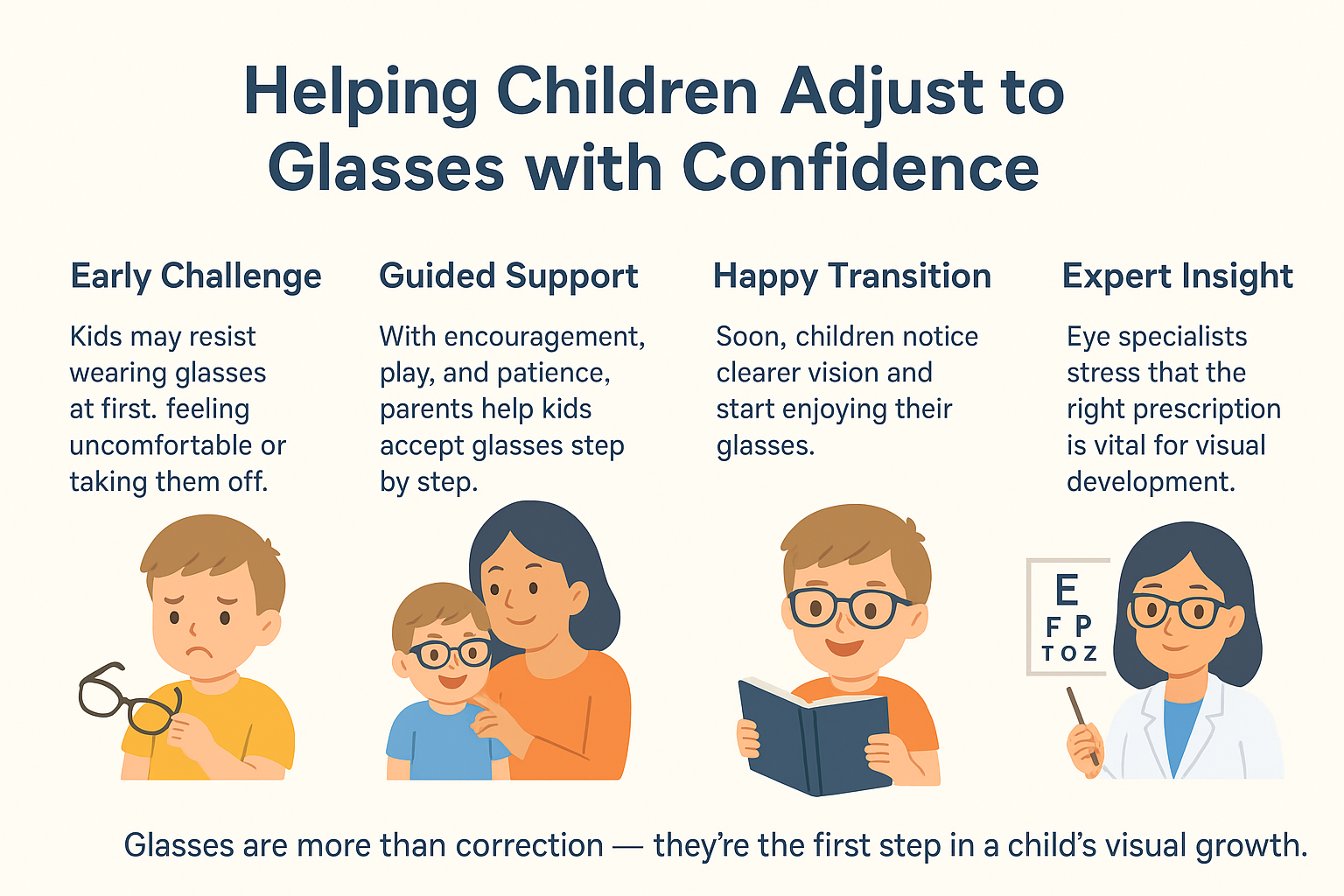

Early Adaptation to Glasses: Overcoming Initial Resistance

- Initial Struggles: At first, the child resisted glasses, removing them immediately after being put on.

- Adaptation Process: Persistence, distraction, and parental efforts eventually helped the child adapt comfortably.

- Positive Response: Child soon preferred glasses and cried when they were removed, showing visual clarity with correction.

- Lesson Learned: Proper prescription helps children adjust quickly, key to visual rehabilitation for children.

- Specialist View: Vision rehabilitation specialists note spectacles as vital in low vision rehabilitation and therapy.

Long-Term Improvement: How Visual Correction Supports Overall Development

- Progress with Glasses: Regular use reduced nystagmus, improved fixation, and boosted interaction with surroundings.

- Cognitive Benefits: Enhanced vision stimulated mental status and supported overall developmental gains.

- Developmental Outcomes: By four years, the child could walk, talk in basic sentences, and show improved motor skills.

- Vision Changes: Refractive error decreased slightly, and eye stability improved with early low vision rehabilitation.

- Rehabilitation Impact: Visual rehabilitation for children demonstrated how sensory correction boosts overall development.

- Case Example: This case demonstrated how visual rehabilitation therapy in children not only improves eyesight but also catalyzes global developmental progress.

Also Read: Blocked Tear Duct in Babies: Causes, Symptoms and Treatments

Conclusion: Optimizing Sensory Inputs for Better Development

In conclusion, this case demonstrates the need to evaluate all sensory systems when dealing with a child with developmental delay. It also highlights the need to optimise the sensory inputs to achieve better overall development. On the ocular rehabilitation front, it highlights the need for proper refraction, early prescription of glasses and need to counsel parents to ensure acceptability of spectacles.

FAQ About Visual Rehabilitation And Developmental Delays

Q1. At what age should visual rehabilitation start for a child with developmental delay?

Visual rehabilitation is most helpful when it starts very early, soon after a child is found to have a developmental delay. Early years are considered the best time because children’s brains are still growing and can adapt faster. A center for visual rehabilitation usually advises parents to begin support in the first few years of life.

Q2. What is Vision Rehabilitation in a Child?

Vision rehabilitation in a child means a step‑by‑step plan to improve how the child uses sight in daily life. It may involve exercises, training, and special tools that build focus, tracking, and processing of what the eyes see. A vision rehabilitation specialist works with families to guide them in improving these skills.

Q3. Why Vision Rehabilitation Matters in Developmental Delay?

When children have a developmental delay, they often face problems with visual learning, and this affects both study and social growth. Vision rehabilitation therapy helps them slowly build visual skills, making simple tasks less difficult. It supports children in gaining better control of reading, writing, and play activities that depend on vision.

Q4. What are the most common eye problems in children with developmental delay?

Children living with developmental delay may struggle with strabismus, refractive errors, lazy eye, and poor visual processing. These problems can make reading, writing, and object recognition harder for them. Many of these children benefit from low vision rehabilitation, which supports them in learning and becoming more independent.

Q5. Is vision therapy effective for children with developmental delay?

Vision therapy can often help children when it is guided well and followed with patience. It may not fix every visual problem, but it improves attention and coordination of the eyes. Visual rehabilitation for children has shown progress in both simple school tasks and daily activities when done regularly.

Q6. How does vision correction help in occupational therapy?

Vision correction gives children clearer sight, which helps them in occupational therapy while writing, balancing, and handling different objects. Better vision makes work easier, reduces strain, and builds confidence during practice. Often, therapists plan programs together with a vision rehabilitation center so the child shows steady growth.

Q7. How long does it take to see results from visual rehabilitation?

The time to see results is never the same for every child, as it depends on age, condition, and how regular therapy is followed. Some children show better progress within months, while for others it may take much longer. With constant support, visual rehabilitation helps improve growth and learning over time.

![DigvijayProfile[1]](https://drdigvijaysingh.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/DigvijayProfile1.jpg)